The Meaning of Success: Kelvin Tan and a Never Ending Story

Words by Isaac Yackem and JX Soo

Photography by JX Soo

From his halcyon days as a key member of pioneering indie band The Oddfellows, to his ongoing chameleon act with a prolific output numbering over 150 releases, Kelvin Tan’s music has always charted his own Singaporean story. But even as he finds himself with stories to tell across Singapore's scene, the singer-songwriter and his work remains curiously under the shadows.

Off the back of 5 releases in 2020 and a well-received show at the Esplanade Outdoor Theatre with The Oddfellows, Kelvin continues to record with vigour, both with his solo efforts and beloved band. Over kopi, Big Duck caught up with Kelvin Tan, as we found out about his story.

Kelvin Tan is an outsider. He always has been, and it seems like he always will be. Yet somewhere along the line, dots always seem to connect him to the stories that have coloured Singapore’s music scene.

As we met at Maxwell Food Centre, we found his hair freshly dyed in shades of pink and blue. At the age of 56, it stood out as a bold choice – but for Kelvin, it wasn’t at all off-brand. After all, the singer-songwriter has operated by anomaly for much of his career. Feasting on kopi and Chinatown’s famous xiao long bao, it’s a fact he recognised, as he began with a corresponding gratitude for the interview.

“I’d imagine there aren’t many people your age that would be interested in what I do!”, he frankly admits with a smile. A former lecturer at institutions like Lasalle College of the Arts, Kelvin is most likely known to the younger generations in his role as a teacher. Performing with his band, The Oddfellows at the Esplanade, a few of his students sat in the audience, many of them greeting him as a mentor.

But his teaching gigs have always been fuel for his own prolific creative endeavours. Sparked with endless creativity since the 1990s, Kelvin's work has sprawled vast dimensions – beyond a musical output spanning over 150 releases, his forays have also delved into photographic and literary efforts: writing two novels, poems, and various plays.

When it comes to his musical story, Kelvin's journey is impossible to tell without his chapter with indie rock trail-blazers, The Oddfellows. Brought into the fray through a fateful meeting with frontman Patrick Chng at a film festival, Kelvin joined as guitarist in 1991, becoming a key member as the band rose to prominence, from outcasts to celebrated pioneers. The role he played in the band, however, was also an unconventional one. Unlike much of the indie rock background his fellow band members shared, his influences came from a lineage of singer-songwriters, brought up on the likes of Jackson Browne and Neil Young.

Himself bringing an outlier sensibility to a band, at the time, working at Singaporean rock's fringes, the Oddfellows found both an unpredictable edge and a learned instinct. “Somehow I always had a punk sensibility even though I was a singer-songwriter first!,” he muses. As The Oddfellows performed at the Esplanade, it was a contrast he displayed magnificently, effortlessly transitioning from heartfelt indie-pop crooning to a blistering, bottle-necked solo. Unleashing a frenzy of noise and feedback, the notes ripped into his fingers, as blood fell onto his strings.

With their differing sensibilities, it was a love of music that bound the unit together, and helped bring them to prominence. Part of it came through in his friendship with head honcho of landmark music magazine BigO, Philip Cheah – one struck up over their preteens, becoming fast friends over frequent cassette listening sessions. As BigO emerged in 1985 with Cheah’s brother, Michael, The Oddfellows found themselves championed as one of Singapore’s first popular indie acts. As a result, their 1991 radio hit, So Happy, became a mainstay within Singapore’s alternative music canon.

“But before that, we came out of nowhere,” he remarks, reminded about the disapproval they faced at the time from the thrash and grunge scenes. “There would be no Oddfellows if there was no BigO,” Kelvin contemplated. As they became championed amongst the community, their brand of indie rock paved the way for Singaporean music to come, opening the doors for other contemporaries like the Padres.

But outside of his work with The Oddfellows, Kelvin’s musical endeavours have always had a difficult time finding an audience, rendered inaccessible through their experimental nature and sheer volume. Nevertheless, his prolific nature has become a calling card for him as of late. Inevitably, our conversation immediately wanders into tidbits about them. As we began discussing his latest batch of five albums, all written and recorded in 2020, he details its improvised process – a constant throughout his myriad of works.

Kelvin’s improvisational avant-garde band from the 90s, Stigmata. Its lineup consisted of Kaye (now of Darker Than Wax fame), now renowned painter/bassist Ian Woo, and Kelvin himself. Photo: Kelvin Tan

Asked about what pushed him towards improvisation, he recalls a life-changing experience listening to the Sex Pistols in 1978. Since then, improvisation became a conduit for injecting a punk spirit into his more conventional singer-songwriter background. The result has brought him through projects spanning a huge array of genres, from solo outings to full bands – the experimental likes of Stigmata (alongside the likes of KAYE and Ian Woo), or Pharmakon (with George Chua and Robin Chua).

“Improvisation is magical - it helps you muster courage.” Kelvin notes. Naturally, some exceptions amongst his discography feel more conventional to form, like a humorous folk stomper in “I Hope I Don’t Get the COVID”. But on other outings, this courage is evident, as Kelvin's explorations stretch far further into left-field – from abstract electronic textures on Being in the Light of Convergence, to In (Ether)’s harsh industrial soundscapes, to Alone, Descending … Sisyphus’ extended free folk jams. Today, he finds himself bored by conventional folk music, with a majority of his work over the past 20 years crafted through daring, improvised processes.

Within this process, no constant came more irreplaceable to his work than the legendary TNT Studios. Here, he notes fondly about TNT’s owner, Wong Keng Kok, who helped level the playing field for independent artists. Insisting on paying bands even in the face of resultant losses, while also maintaining an affordable recording rate, bands found it possible to record on a tight budget. Becoming a pivotal figure through organising shows and maintaining his signature venue at Parklane Shopping Mall, he became affectionately known to the underground scene as Ah Boy.

Close friends with Ah Boy since his long-haired days, TNT became the place where Kelvin exclusively recorded his massive catalog of work, all the way back to his days with The Oddfellows. His new slate of recordings were no different.

“During the circuit breaker, I thought to myself that it would be great to just show up at Ah Boy’s with just a guitar, mic, and no plan - to just make music.”

Today, Kelvin still loves jamming to the jangle-infused indie rock that has made him a name – cherishing the friendship they share as a unit. “The Oddfellows to me are more about having fun and living by example,” Kelvin notes, sharing their plans to return back to TNT for new recordings for the first time in years.

Yet at the same time, he is also eager to continue pushing his sonic boundaries independently. While most of his contemporaries are content with solely listening to the music of their youth, Kelvin is most excited about discovering and creating fresh sounds. “The Oddfellows are family – but dammit, I wanna make black midi meets Tennis too!”

Asking Kelvin what he’s been listening to recently, the replies are impressively diverse – some entries which would not have been out of place from collections of fans brought up in the internet age. Citing his favorite artists, he namedrops Fontaines D.C. and Kanye West, while his rotation heavily features garage rock like Ty Segall and avant-garde jazz the likes of Jeff Parker. Perhaps even more surprising was his love for a handful of lo-fi indie darlings: Alex G, Elvis Depressedly, and Deerhunter amongst many.

But at 56 years old, Kelvin finds himself in an even more awkward position with his youthful outlook - a middle man sandwiched within the generational gap that separates the pioneers and gatekeepers of his time, from the current wave of Singaporean music. It’s a state that he laments and protests against.

“I hate the word ‘present’, because music is just music in the end, no matter who’s making it,” he sighs. By embarking on a more adventurous path, both sonically and in life, Kelvin finds himself alienated from many of his peers, who have chosen to take on more conservative or stable roads. In the same vein, he holds disdain for many of his contemporaries who frame young people within certain archetypes.

Yet at the same time, many younger musicians and potential listeners also write Kelvin off due to his age. It’s a reality he hates, believing that ageism has robbed many from countless connections with others. “So much art has been destroyed because of it,” he laments. But his views come far from criticising the current generation. In fact, as our conversation drifts towards Singaporean music today, parallels surface between the past and the present.

Bringing up the past, Kelvin brings out gifts for us. He hands us both a personally dedicated copy of his debut solo album, The Bluest Silence. Kelvin points out that The Bluest Silence shares its producer, Jason Tan, with one of our favourite albums of 2020 - .gif’s Hail Nothing. He begins to give me some context to Jason’s musical background. Helming Convent Garden, one of Singapore’s first few electronic bands, he describes Jason’s nature as a master of everything, one he experienced himself when making his debut.

“He’s a total tech guru and musical genius, really - but he’s got a tyrannical grip on the creative process!” he remarks. It's an experience he believes that he shares with .gif’s own production process – with Jason’s pristine, Sylvian-like sonics colouring Hail Nothing’s masterful beats. Examining his past collaborators from his age, many have also reemerged in the scene, making their mark in their own ways: whether it be KAYE running celebrated electronic imprint Darker Than Wax, or reemerging sound art pioneer George Chua. Yet even as his friends and peers emerge, Kelvin's work has always been caught somewhere in his own lane, on a radar separate from the rest.

Nevertheless, he doesn’t miss the elitism he observed in different scenes of old, one he recalls from his encounters with certain obstinate members of the metal scene. “Someone would say ‘You like Slayer ah?’ But he doesn’t actually want you to be a Slayer fan, because he wants to be known as being the ‘real’ Slayer fan,” Kelvin elaborates. As a result, many were caught in a chase of virtuosic calisthenics as competition – a speed race that Kelvin was grateful that he didn’t get caught up in.

Kelvin’s gifts: A print copy of his first novel, 'All Broken Up and Dancing,' and a CD of his first solo album, 'The Bluest Silence.'

Kelvin makes his disdain for that mindset clear. Without a doubt, his guitar ability is evident – demonstrated aplenty on both his performances and albums, like 2016's Where the Real Lions Are ….. But he is quick to emphasise the importance of songwriting and musicality, an ability he believes that the chops-obsessed scene he grew up in greatly lacked. “I’m glad for my diverse musical upbringing. It allows me to shred if I wanna shred, but there’s no point if it isn’t musical,” he says.

"I think it’s tied to the academic system here in Singapore, that culture of competitiveness.” Distilling that experience into advice for new, aspiring musicians, he emphasises the importance of knowing one’s agenda with music.

Even when left with a tiny audience today, Kelvin seems to have already accepted the way things are. Finding the open-mindedness of youths more comfortable, he enjoys discussions with the new generation more than those with his contemporaries, who often have left behind their experimental inclinations with life’s changes. As he brings up the past, he begins joking about his own peers, casting many of them off with a disappointed laugh.

“My generation is a disappearing generation, and I’m not sad about it. We have a different way of life, and I can’t talk with them about music anymore. They’re high-class coolies without the pigtails!” Kelvin jokes with a wry smile. He comically mentions how he now avoids reunion dinners with his former schoolmates, dreading reliving a soundtrack full of only throwback 80s hits.

At this juncture, I ask him if he feels that he has accomplished success in what he wants to do with his music.

He answers with a resounding yes.

Kelvin then tells me of the time he met and sat across Kurt Cobain in Singapore in the 90s - one year before he killed himself. Reminiscing, he leans back and sighs.

“Even though it still saddens me, I can understand why he killed himself. He thought that if he got fame and success he would be happy, but it actually made everything worse - his life ran out of meaning. I know my music is inaccessible, but in the end, I do it for myself,” Kelvin says with conviction, “Not a lot of people are listening to it, but there are people who do, and that’s what matters.”

Kelvin’s Nevermind cassette signed by Kurt Cobain when Nirvana was in Singapore. Credit: Kelvin Tan

Kelvin considers himself a success by the definition of Bob Dylan - defined by continuing to do what he wants to do. “I’m a songwriter, but am simply not called to certain things such as making it big or going on tour,” he confidently proclaims. “If successful means that I’ve lived a meaningful life, that means I’m successful. Having that meaning in life is an underrated trait.”

It’s a raison d’etre he applies to his music, through insisting on constant exploration. “My music is an attempt to find an alternative voice. Sometimes you fail, but part of the process is failing – after all, the great playwright Samuel Beckett said ‘fail better’. As a musician, I think that’s what it’s all about: failing better.” With the COVID-19 pandemic forming a reset for the music industry, the need to look for work and make a living still exists for Kelvin. Even so, he finds refuge in continuing his art-making. “I’m not so worried about that. I’m still doing what I do even when I’m in my 50s. I take heart in that - to me, this might be part of the journey to something new."

With a keen eye attentive to Singapore's music scene today, he believes that artists as of late are capable of creating a new potential renaissance in the scene. As our conversation moves towards the present, Kelvin lights up, as he expresses a strong desire for chances to work with those from the new generation. Of these, he mentions FAUXE in particular – admiring and sensing a common soul with the producer’s open-minded spirit. But beyond FAUXE, he also finds himself excited at the idea of working with anyone musically open to new ideas.

Above all, he believes in those dedicated to the art of songwriting. With a laugh, he even states more absurd examples. “If Justin Bieber called me up for a collab, I would totally do it! It would be fun!” Kelvin amusedly says.

Having taken the road less travelled, Kelvin shares a complicated relationship with his home of Singapore, especially in regards to the arts. “I’m proud of what Singapore has achieved, but suffering because of what’s been taken away from us,” he confesses. Acknowledging that the Singaporean system desires quick fixes, he laments the lack of infrastructure and continuum for music here to grow.

Compared to countries like Taiwan or Japan, he believes Singapore largely lags behind due to its lack of deep cultural awareness. He connects part of it to Singapore’s repressive history – as policies were enforced to crack down on the music scene’s rowdy behaviour and drug use, Singapore’s music scene saw an extended drought of sonic invention, brought about by a destroyed music industry. This, he believes, has led to ignorance and relative inexperience from the Singaporean government’s arts sector.

“Singapore’s rise has been methodical, but at the expense of having our cultural awareness curtailed,” he says. “Because our punk scene got wiped out, Singapore’s arts sector is run by bureaucrats, rather than former punk and scene kids that grew up.” It’s a fact he regrets, noting the work of Singapore’s thriving music scene in the 1960s, led by bands such as The Quests, The Siglap Five, and The Cyclones. I ask him whether he thinks sacrificing the development of the arts to ensure our survival was worth it. He ponders for a moment, and as he replies, a smile emerges.

“That’s a good question. Unfortunately, I don’t know.”

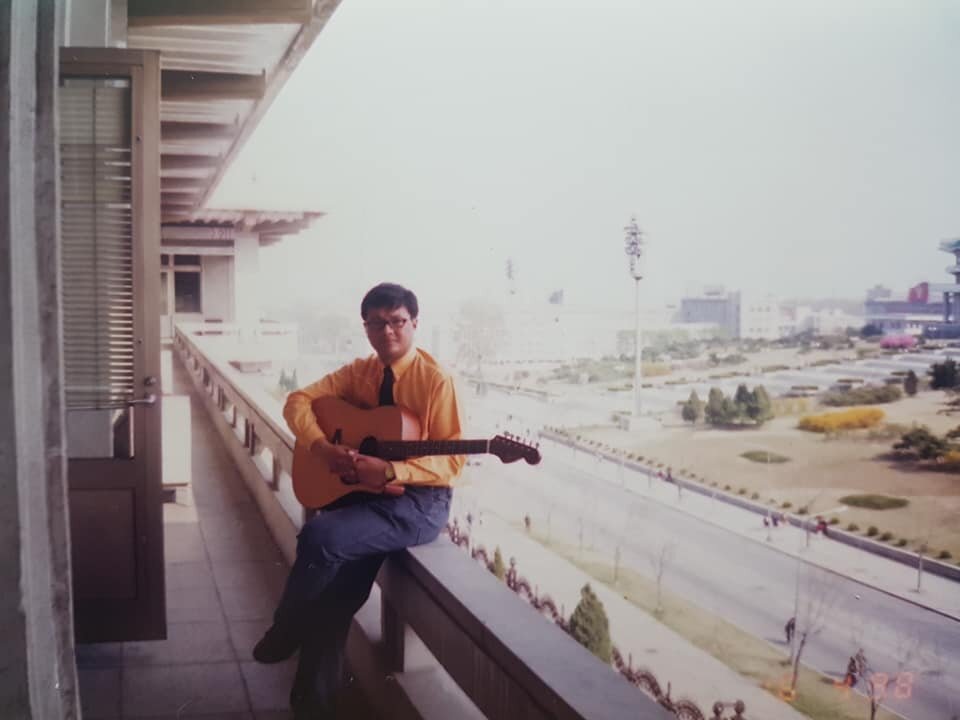

One day, Wong Kwang Han, his friend, informed Kelvin that Aporia had received a letter from the North Korean embassy. Inside contained an invitation to perform at the 16th Spring Arts Festival in Pyongyang - but initially, Kelvin was in disbelief.

“Nonsense!” I said. It’s not a good idea to joke about things like that. But he showed me the letter and there it was - I guess we sounded communist or something!” Kelvin laughingly remarks.

Kelvin’s performer’s pass for the 16th Spring Arts Festival in Pyongyang. Credit: Kelvin Tan

An eventful trip followed. Without direct flights, the entourage proceeded to Beijing to be picked up by an old 1940s style plane, only for their passports to be immediately confiscated upon arrival. “It was scary, because there was no way we could leave the country then,” he recounts.

Originally thinking they were to be taken to the hotel, they were instead put into a van, driven far into the dark North Korean countryside. Spooked without knowing what was going on, the drive continued for hours, until their purpose was revealed – to present a bouquet of flowers and bow down to a statue of Kim Il-Sung.

Diving into the experiences with the North Korean people that he met, he noted the haunting cognitive dissonance they possessed. “There was one time on the bus where we were all given some apples to eat by our interpreter,” he recalls. “She asked us how the apples were. One of the German singers told her that they were ‘not bad’ - but as the interpreter heard their words, she promptly began chastising them. “Not bad? Why not good? Did you know our great leader planted and grew these apples for you to eat?” It would be the last he would see of them.

As part of a cultural exchange, Kelvin then found himself having to learn a song about Pyongyang to honour then Leader Kim Jong-Il, and one “Singaporean song” to represent his homeland. Over a two-week-long stay, it served as the setlist to his several performances in North Korea, amongst which include showcases in front of North Korea’s late Leader, Kim Jong-Il. To represent Singapore, Kelvin chose the classic national song Di Tanjong Katong.

While frightening, the trip was an eye-opener for Kelvin – one he does not regret having embarked on. “It’s the only Stalinist country in the world, and for two weeks, I lived there! North Korea changed my life, and above all, it made me appreciate Singapore a lot more,” he reflected.

As we end our chat, he cracks up with a wide grin.

“Plus, how many people can say they’ve played in North Korea? Even the Rolling Stones haven’t played in North Korea!”